With the knowledge that we had been rehearsing in spaces considerably smaller than the Auditorium at Lincoln Performing Arts Centre, my main priority for show day was to sort out the staging for The Truth About Bedtime…, in particular the movement scenes. i knew it was important to make sure that the movement I had created really filled the space, and that every little detail had been thought about on my end. To ensure that this process ran as smoothly as possible, I staged the scenes in chronological order, getting the company to mark through the scenes after assigning them their new staging positions. The purpose of marking the scenes through was to ensure that each movement was clearly visible for the audience to see, and so the company members knew exactly where to go.

The lead up to the final performance was well organised by stage manager, Chloe McKay, allocating time for a dress run where director Emelia Hutchinson, who did not perform, was able to write notes about the staging on my behalf. There was also time afterwards where I could correct any errors that occurred. Before the show began, I made sure that the entire company participated in a physical warm up, including breathing exercises and stretching the body.

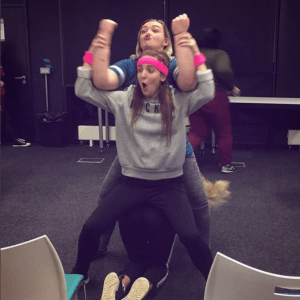

After finishing our final performance of The Truth About Bedtime…, we were overjoyed with the response and feedback we received from our audience. The Exercise Scene received a round of applause from the audience which, as choreographer, filled me with happiness that I had created choreography that was enjoyable for an audience. The decision to hold back on energy in the opening numbers in rehearsals turned out to be the right decision, as the energy from the company on show day was thriving.

Arts Council England are interested in offering “new experiences” (2018) for audiences, something I believed we created during our pre-set. Where usually audiences enter a theatre space greeted by an empty stage, our decision to interact with the audience members during our pre-set meant that we could really take control on ensuring that our audience were fully catered for. Audience were immediately greeted as they entered the space and three company members were allocated a seating side each.

Of course, there were things that I would have changed. ‘Lucid Dreaming’, for example. lost the synchronisation we had created in rehearsals in such a big space. This was an unfortunate occurrence which we could not have foreseen, as we felt that we had prepared enough to be able to adapt to a new, bigger space.

Overall, I was extremely proud of the professionalism of the company and how they dealt with such a high intensity physical performance that I had created. Seeing my choreography come to life was heart-warming and rewarding, and I am eternally grateful to Sherbet Lemon Theatre for helping my crazy ideas come alive. Here are a few of my favourite choreographed moments from The Truth About Bedtime…

L.R.

Works Cited

Arts Council England. (2018) Supporting arts, museums and libraries. England: Arts Council England. Available from https://www.artscouncil.org.uk/what-we-do/supporting-arts-museums-and-libraries [Accessed 19 May 2018].

Sired, K. (2018) Exercise machine show day [image].

Sired, K. (2018) Lucid dreaming [image].

Sired, K. (2018) Mr Sandman 1 [image].

Sired, K. (2018) Mr Sandman 2 [image].

Sired, K. (2018) Night terrors [image].

Sired, K. (2018) Sleep paralysis [image].

Sired, K. (2018) The exercise scene [image].